But is it really that simple? In any given month, we have only a rough approximation of how many people are unemployed and an even rougher idea of how many might become employed but are currently not even looking. The numbers come from survey data, with all the inherent limitations surveys entail. There are actually two different federal surveys, and sometimes they disagree wildly. Over time they get in line, but on a month-to-month basis? Not so much. Beyond those surveys, what we think we know is mostly conjecture and assumptions about what we want the data to say.

For instance, simple observation and the actual surveys suggest that many Americans, while nominally employed full-time, aren’t earning as much as they once did. Nor are they as productive as they once were or as they could be. If that’s a widespread pattern, it means the economy still has “slack.” Production could rise significantly without adding any new workers. What we have is not “full employment” in any real sense.

We use survey data to infer how many people are employed, how much they are paid, and so on. In the process we observe people who aren’t employed. We try to figure out why they don’t have jobs and what circumstances might bring them back into the labor force. It’s a many-faceted mystery no one has solved, yet we make important policy decisions based on our fragmentary understanding of that mystery.

Let’s look at a few different ways to measure what we mean by full employment. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) suggests that if you haven’t been looking for a job in the last 30 days, you are not in the workforce. Thus you don’t count as unemployed.

First off, that way of defining unemployed runs contrary to all of our personal experiences. There are lots of people who have not been able to find a job and have given up looking, but if they were offered a decent-paying job they would take it. Choosing to say that they are no longer in the labor force after just 30 days of not looking seems rather arbitrary and unrealistic to me.

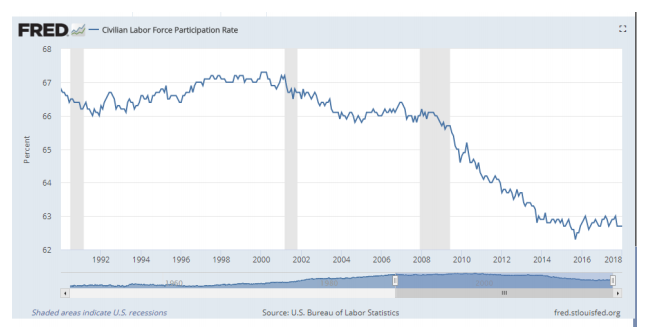

Now let’s take a look at the U.S. labor force participation rate since 1990 via the St. Louis Fed’s FRED database: