That proved to be a great time to buy Berkshire stock. This time is trickier. The market only looks as good as it does because of the internet giants, and Buffett surely cannot pile in at these levels. But if he really finds nothing else appealing at current valuations, it implies that the Fed will have to let the market fall a long way before Berkshire can start to deliver.

Buffett has some problems, in that he has become virtually a one-man signaling machine. The fact that he abandoned his normal breezy demeanor helped depress the market (before the FANGs, currently even more powerful than he is, turned things around). Whether he wants it or not he has a certain responsibility these days. But for the most part his incentives are fairly straightforward —he deploys Berkshire’s cash if he’s confident he can generate a great return, and otherwise he leaves it where it is.

Before Berkshire, he was a pioneer managing investment vehicles that would come to be known as hedge funds. And this market is really giving them fits. Research published Monday by Epsilon Asset Management’s Faryan Amir-Ghassemi and Michael Perlow, and New York University’s Andrew Papanicolaou lays bare the problem.

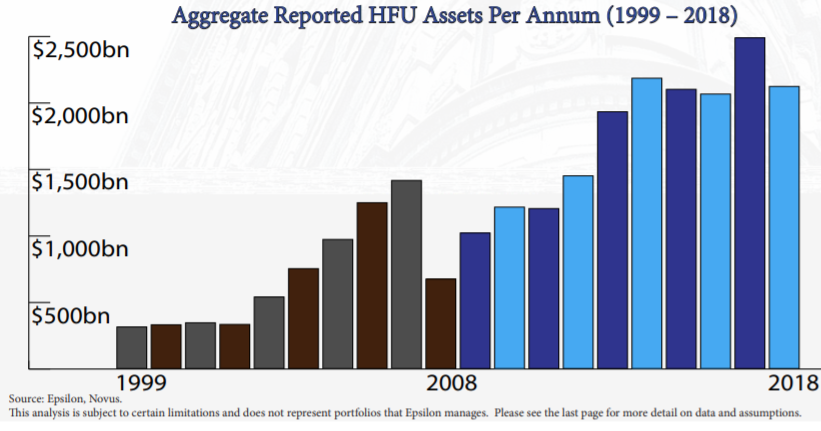

Hedge fund managers want to attract funds, and to produce the over-market returns that trigger their performance fees. Over the last decade, they succeeded greatly in the former, and failed miserably in the latter. These things are almost certainly related. This chart shows the total funds managed by the equity hedge fund universe, as examined by the team at Epsilon:

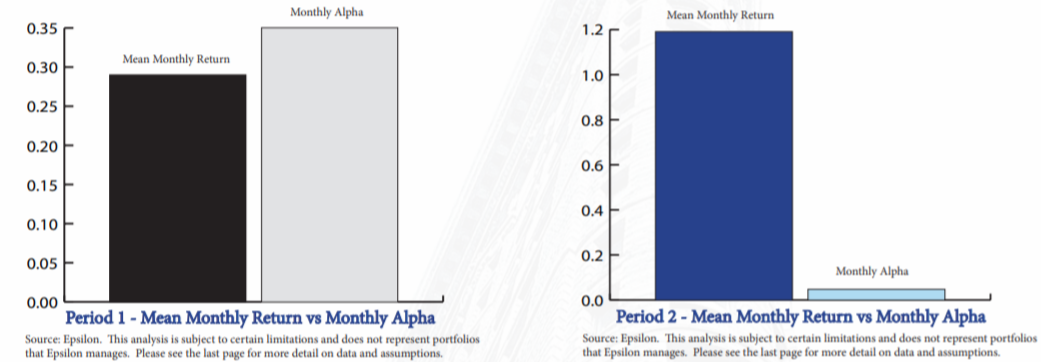

In the decade starting in 1999, the hedge fund industry was still more or less composed of opportunistic vehicles of the kind Buffett used to manage in the 1960s. Over the following decade, they morphed into something bigger, more institutional, and ultimately slower and clumsier. This is what happened to equity hedge funds’ alpha (or ability to deliver returns over and above the market):

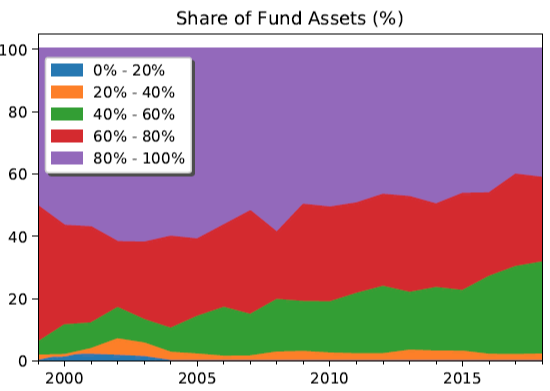

Note that these returns are before hedge funds’ exorbitant fees. So the offer is (very) ordinary performance for extraordinary fees. Part of the problem is that as funds have grown bigger, so they have tended to hold larger stocks, and tended to move closer to the overall index. The following chart measures funds by their “active share,” or the proportion of the portfolio that is different from a direct holding of their benchmark index (so a well-run index fund would have a 0 active share, and a concentrated portfolio of micro-caps not included in the index would have an active share of 100). Hedge fund managers are much more truly active than mutual funds, but they have steadily grown less active as time goes by.

This leads them to a horrible dilemma. There is an old market cliché that nobody ever got fired for holding IBM. But no hedge fund is ever going to be hired for holding FAANG stocks. Exposure to such companies can be bought far more cheaply in an index fund. If a fund manager truly believes in Microsoft, for example, there is really no point on acting it unless he or she is prepared to make a huge bet, putting 10% or more into one stock. But against that institutional incentive to avoid the FAANGs is the cold fact that the best way to make money this year has been to hold them.