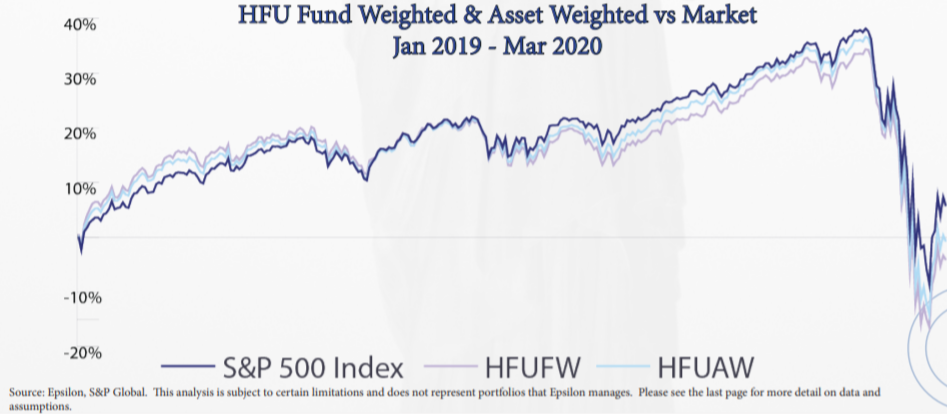

This has at least led to one interesting reversal of fortune. The following chart shows Epsilon’s index for equity hedge funds weighted by volume of assets (HFUAW) and by funds (HFUFW). The first can be viewed as an equivalent to the cap-weighted S&P 500 and the latter to the equal-weighted S&P 500. The same thing is happening to hedge funds as to the market as a whole. Usually the smaller, nimbler ones do a bit better. At present, the big ones are outperforming (although they are still failing to beat the S&P 500). This may be because they are doing a better job of guarding against downside in a sell-off.

Alternatively, it is because the big hedge funds have more money salted away in the FAANGs. Either way, everyone agrees this is an impossibly difficult market. To Warren Buffett and the hedge fund industry, add Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s David Kostin. The investment bank’s chief U.S. equity strategist drew up the dilemma in stark terms this weekend:

the five largest companies collectively account for 20% of S&P 500 market cap, the highest concentration in more than 30 years. Although the index trades just 14% below its all-time high, the median S&P 500 constituent still trades 23% below its record high…

Eventually, narrow market breadth is always resolved the same way. Often, narrow rallies lead to large drawdowns as the handful of market leaders ultimately fail to generate enough earnings strength to justify elevated valuations and investor crowding. In these cases –such as the experience with the five largest stocks in 2000–the market leaders “catch down” to weaker peers. In other cases, improving economic outlook and strengthening sentiment help laggards “catch up” to the market leaders. In both cases, the relative outperformance of market leaders eventually gives way to underperformance.

It’s impossible to disagree. But Kostin also cautioned, correctly, that “timing the reconciliation is difficult.” These are horrible conditions for active managers.

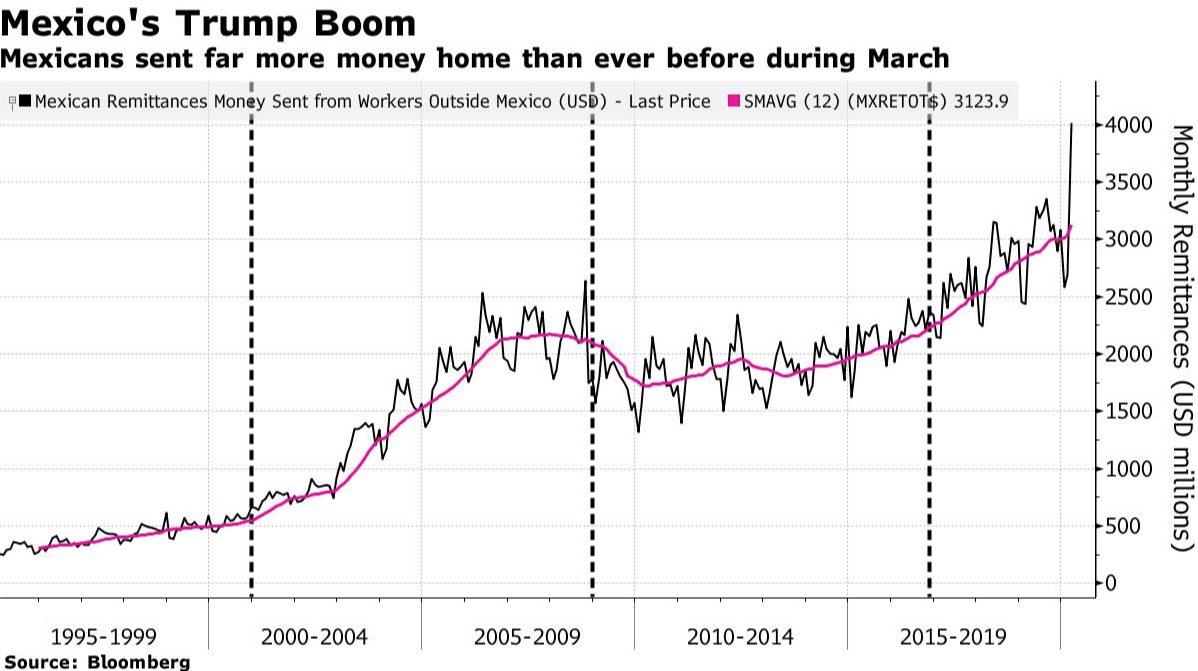

Money Goes South

How to explain this amid a sudden recession in which many migrant workers will have lost their jobs?

In part, they are reacting to the exchange rate. With the peso falling to record lows, this is a windfall for their families. It’s also possible that many are preparing to go home, and are getting their houses in order. There was a similar spike as the Great Recession was taking hold, followed by years of declines.

Surprising statistic of the day: The amount of money Mexican migrant workers (almost all in the U.S.) send home in remittances has hit an all-time record. After staying flat through the eight years of President Barack Obama, remittances were already rising strongly under President Donald Trump. In March, the monthly total topped $4 billion for the first time, barely more than a year after reaching $3 billion: