Our holiday from history has come to an end. I am referring not to world peace but to the zero-interest-rate environment so many people expected would last forever. Despite all the talk about when the U.S. Federal Reserve will cut rates and bring back those holiday vibes, there is a very real possibility that it will not matter when the cuts happen or how many there are.

That’s because the interest rates that matter for much of the economy—longer term U.S. Treasury bills—may not just be higher for longer: They may be higher forever. And that would mean a new era not only for investing but also for the economy.

While the Fed exerts control over short-term Treasurys, the research is mixed on how much influence it has on longer-term bonds. And the 10-year is what matters for how capital is priced and what rates consumers face. Its price tends to be driven by macro factors: the growth and inflation outlook of the economy, global and domestic demand for safe U.S. assets and, usually, the long-term debt of the federal government.

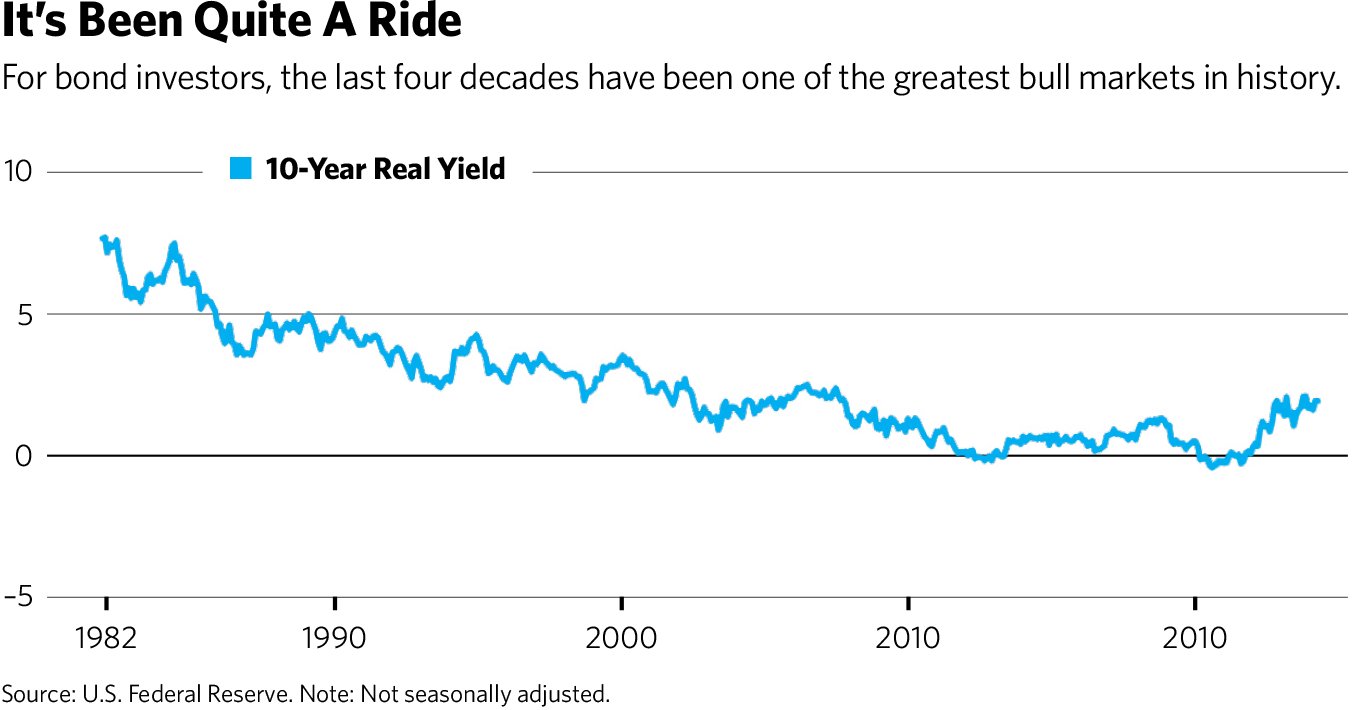

But on our holiday from history, the bond market appeared to have entered a new era. No matter the economic environment, yields went down and so prices went up: It was one long bull market. To some extent, this was justified by a low-inflation environment, an insatiable demand for U.S. debt from foreign governments, and various regulations that prized U.S. bonds as the world’s safe asset.

But bonds aren’t like stocks. Rates can fall only so low—no one will buy a bond that offers a negative 8% yield. In the 2010s, real rates hovered around 0%, in spite of the government piling on debt and a waning appetite for U.S. debt from its more reliable buyers. But that may have been an anomaly. Research on the 10-year yield going back to 1300 shows how it trended down as the world got safer and financial markets deepened. At the same time, the bond market has always had periods of highs and lows, and rates tend toward the mean.

The last 10 years was one of those low periods. Today, macro forces will probably push rates back up to 4% or more: A higher and more volatile inflation environment is back, the government must issue more debt to pay for an aging population and ambitious industrial policy, and “deglobalization” will weaken demand for U.S. assets.

In short, there will be more debt, and it will be riskier. That means there will be less demand. Even if rates fall in the short term, there is a good chance they will settle at a higher level.

That would change everything about the economy as we know it. Bill Gross, the man who got very rich running bond funds during one of the greatest bull markets in history, declared his strategy was “dead.” My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Aaron Brown convincingly argues that there are still good reasons to invest in bonds, but Gross is probably right that it no longer makes sense to look to bonds as both a hedge and for consistent high returns.

In retrospect, it seems clear it wouldn’t last. But the bond market of the last few decades made it possible to believe we lived in a world with no trade-offs. Governments could borrow money to spend or cut taxes. Venture capital and private equity, flush with cash seeking a positive yield, did not have to be so particular about where they invested. Low interest rates buoyed stock valuations. Firms could lever up and expand without a worry how it would all be paid back.

The return of the high-rate environment means that, once again, investment has more of an opportunity cost and downside risk.

It is not all bad. A higher-rate environment doesn’t necessarily mean less investment, for instance; some of history’s most robust and productive periods took place when rates were higher than they are now. A higher-rate environment will also encourage a healthier relationship with risk. Bond yields are the foundation of how risk is priced and measured, and a zero-rate environment distorted our relationship with it.

And while mortgage rates and interest on auto loans and consumer credit will be higher, there are some benefits to consumers. Savers will once again get a positive yield for investing in low-risk assets—at least before inflation. The biggest beneficiaries will be retirees, most of whom have paid off their mortgages and have more assets. Higher rates will mean their money goes further in retirement. For at least one segment of the population, returning to real life after the holiday won’t be so painful.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.