Deteriorating global growth prospects amid heightened uncertainty about global trade have led to a dramatic shift in monetary policy direction this year. A growing number of central banks have already eased or are considering easing monetary policy, ending a brief period of intent to bring interest rates and balance sheets back to normal levels.

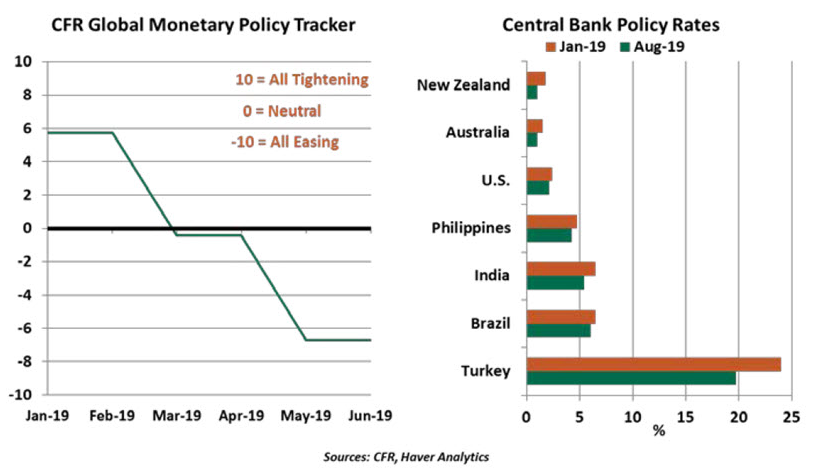

More than 30 central banks across advanced and emerging markets have cut interest rates this year. The Council on Foreign Relations’ Global Monetary Policy Tracker, consisting of data from 54 countries, reversed its course in January 2019 and has trended easier ever since. In August, central banks in Mexico, India, Thailand, the Philippines and even New Zealand cut their benchmark rates. Mexico’s cut was its first in five years, while the Reserve Bank of New Zealand reached a record low policy rate.

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) hasn’t moved its benchmark interest rates since 2015, but has been deploying other measures to boost the economy. In an effort to improve monetary policy transmission, the PBoC took steps earlier this week to bring average loan rates down.

Among the larger central banks in the West, the European Central Bank (ECB) has explicitly indicated its intent to ease. A recent round of gloomy data combined with rising risks of a no-deal Brexit raised market expectations of a Bank of England cut this year to above 50%. And although it has little room to maneuver, the Bank of Japan has shown openness to additional easing.

With both interest and inflation rates stuck at historic lows in key markets, standard monetary tools may not be enough to boost growth, especially if the slowdown becomes a downturn. As a consequence, currency depreciation could become the default option for transmission of monetary policy. Central bank decisions, in most cases, are not explicitly tied to exchange rate movements, but the line is becoming blurrier.

As an example, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s June meeting minutes mentioned that “the main channels through which lower interest rates would support the economy were a lower value of the exchange rate.” Transmitting policy through exchange rates, intentionally or otherwise, is not only a risky zero-sum game, but would also draw America’s attention.

The challenges faced by those gathering in the Rocky Mountains this week are formidable. They are being asked to counteract restrictive trade policies and offset the secular forces that are reducing inflation. The tools they have at hand are not well suited to these objectives, and deploying them could create distortions in financial markets.

The solution might better come from more aggressive public spending. ECB president Mario Draghi will be missed at Jackson Hole this year, but his remarks from the 2014 symposium that “it would be helpful for the overall stance of policy if fiscal policy could play a greater role alongside monetary policy” are worth remembering. Central banks were the only game in town ten years ago, but other players may need to take the lead going forward.

Spreading Negativity