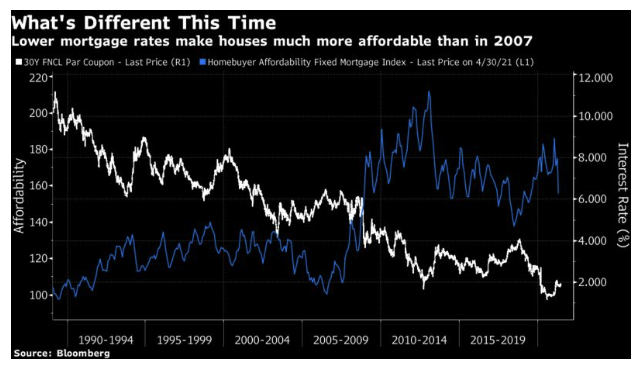

We know what happened after the last great peak, and nobody wants a repeat. However, as in many other market matters, today’s exceptionally low interest rates change the picture. The benchmark Fannie Mae mortgage yield has fallen since the last crisis, in large part thanks to the determined efforts of the Federal Reserve. This means that affordability, defined by how easily someone on the typical income could cover the interest payment on a typical loan, remains unchallenging. Despite a dip in affordability recently, house prices are more manageable than they were at any point in the decade before the crisis:

While there is a lack of available homes, therefore, the rally could yet go further. Capital Economics Ltd. cautions as follows:

These buyers will face strong headwinds this year. Annual house price growth surged to a record high… stretching affordability. Booming values have been accompanied by a sharp rise in house price expectations. That raises the risk of a self-reinforcing bubble forming, similar to that seen in the mid-2000s, as households look to take advantage of rising house prices. That could provide support to sales over the remainder of the year. But with lenders unlikely to significantly ease credit conditions over the next few months, we think a house price bubble and acceleration in sales is unlikely.

Without the crucial extra ingredient of irresponsible leverage, a housing bubble is much less dangerous. And if we look at another bubble indicator, money flows into homebuilding stocks, this incident is nothing compared to what happened 15 years ago:

A sharp rise in house prices always demands attention. But on balance this doesn’t look like a destabilizing dose of speculation.

But What About Inflation?

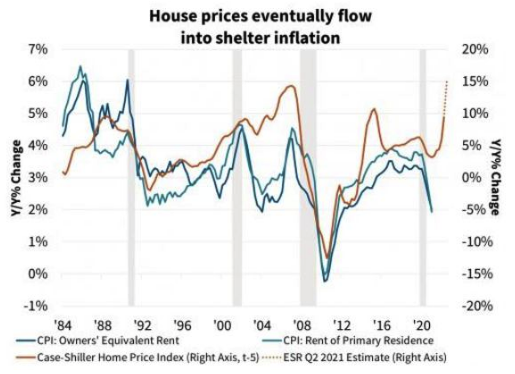

Shelter is still the largest single component of the consumer price index, though. Via their impact on rents, higher house prices affect inflation, but with a lag. The following chart, from a rather sobering paper by Fannie Mae, suggests the CPI components for rents tend to follow the Case-Shiller price index with a delay of about five quarters:

This leads to the issue of the moment, which is inflation. Rising house prices actually increase the buying power of those who already own them, while the cost of financing more expensive homes causes families to cut back expenditures in other areas, so the effect is counter intuitively deflationary.