Analyses of these trends, however one chooses to measure them, tend to focus on the negative implications for economic growth, U.S. geopolitical clout, retirement-system financing and other macro issues. These are valid concerns, but focusing on them to the exclusion of all else can be misleading, as four researchers from Canada and the U.K. described in a paper published recently in the American Political Science Review.

Drawing on a large new dataset of US news content, we demonstrate that the tone of the economic news strongly and disproportionately tracks the fortunes of the richest households, with little sensitivity to income changes among the non-rich. Further, we present evidence that this pro-rich bias emerges not from pro-rich journalistic preferences but, rather, from the interaction of the media’s focus on economic aggregates with structural features of the relationship between economic growth and distribution.

That is, gross domestic product growth, asset prices and other aggregate measures of economic performance offer “a portrait of the economy that strongly and disproportionately tracks the welfare of the very rich,” and doesn’t necessarily represent the experience of everybody else.

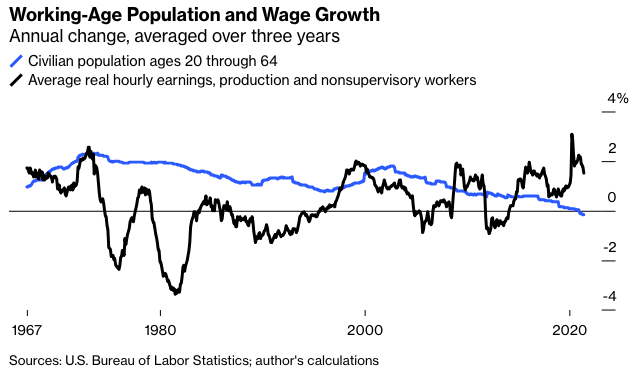

So let’s try an economic metric that explicitly doesn’t track the welfare of the very rich: real hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees. I measured and smoothed it the same way as with working-age population growth (that is, by calculating annual percentage growth over a rolling three-year period), and put the two together on the same chart.

OK, so it’s not exactly a lockstep relationship. But it is a relationship—with a correlation coefficient that nears -0.6 (on a range where one and negative one signify perfect correlation and zero none at all) if you compare population growth with wage growth four or five years later. Which doesn’t prove anything, of course, but it’s interesting that a similar exercise with real GDP growth delivers a correlation coefficient of just about zero no matter how you time-shift the data.

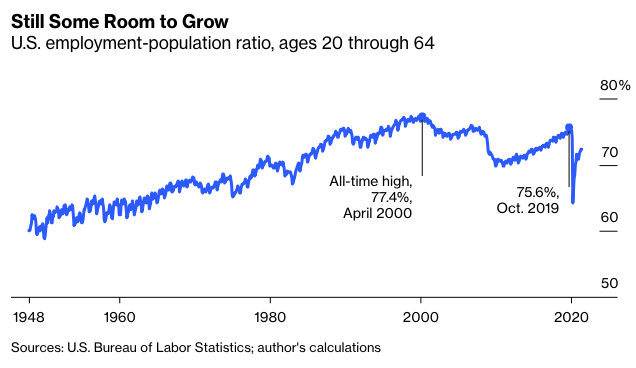

This is also of course what basic supply-and-demand economics would predict. All else being equal, scarcer labor should mean higher prices for that labor, which in turn should spur efforts to improve the productivity of that labor through investment and innovation. All else isn’t equal, and again I don’t think all the worries about the negative effects of a shrinking working-age population are misplaced. Barely positive growth over the long haul is probably fine, though, and over the short-to-medium-term there’s room for employment to grow among working-age Americans even if the working-age population doesn’t.

It’s not just that the current 72.3% employment-population ratio of the 20-through-64 age group is well short of past highs. Even the employment-rate peak of early 2000 should not be seen as the upper bound, J.W. Mason, Mike Konczal and Lauren Melodia argue in a new Roosevelt Institute paper, given that big gaps in employment rates by race, gender, education and age persisted even then. Mason, an economics professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York, has been making a spirited case in multiple venues recently that “there is much more space for demand-led growth in the U.S. economy than conventional estimates suggest,” and that the Biden administration’s ambitious spending plans could bring big labor-force and productivity gains. If that turns out to be right, the stalling of working-age population growth will mainly just be a boon for workers.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.