The outcome of the midterm elections has left lingering uncertainty in Washington, including the question of what fiscal policy might look like in the new Congress. But even if Republicans regain control of the House of Representatives and/or the Senate, the landscape as we close out 2022 is completely different from the end of 2010, when Republicans last took back control of the House.

In 2010, the economy was weak and Republicans believed that they had a mandate to cut spending, which then held back the economic recovery. This year's economy has been affected by a lot of fiscal drags from policies enacted in 2021, but those are unlikely to be a restraint in 2023. On the contrary, there are fiscal boosts already in the pipeline that a Republican Congress won't be able to undo. This is good news if you're worried about Republicans using their levers of power to slow down the economy. It's not such good news if you’re worried about inflation.

The thing to recall about the economy in the years following the 2008 recession is that state and local government finances were in tatters. There wasn't much political appetite for raising taxes to balance budgets when unemployment was high. When Republicans swept to power in 2010 that became even less possible as spending cuts paved the way for state and local governments to balance their budgets. At a time when the economy could have used a boost, state and local governments cut 278,000 jobs in 2011, and Republicans in Washington worked to cut more than $1 trillion in federal spending that same year.

Heading into 2023, the economic situation couldn't be more different. At the end of 2010 the unemployment rate was above 9%. Today, it’s below 4%. And because the economic story of 2022 has been a mix of strong job growth and elevated inflation, it's been easy to forget that there have been drags on economic growth in 2022 due to the absence of some of the fiscal boons from 2021. There were no $1,400 stimulus checks or enhanced unemployment insurance payments this year, and the additional child tax credit included in the American Rescue Plan wasn’t renewed this summer.

Additionally, because financial markets boomed so much in 2021, U.S. taxpayers paid an additional $200 billion or so in federal taxes this year because of capital gains on investments they sold. Without that, the wealthy would have had even more money to spend on things like automobiles, furniture and vacations.

Because financial markets are having a terrible year in 2022, that fiscal drag from capital gains taxes won't exist next year. And unlike in 2011, state and local governments are currently flush with money due to a mix of pandemic stimulus and strong economic growth, and are finally getting around to spending it.

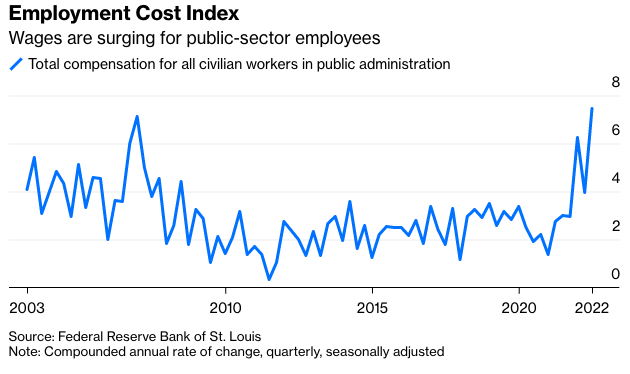

Over the past year, state and local governments have added 263,000 jobs and that pace could pick up in the months ahead, particularly if private-sector layoffs increase the pool of people willing to consider working for the government. Importantly, wage growth for public-sector workers is surging — in the third-quarter Employment Cost Index, total compensation growth for public-sector workers rose at a 7.4% annualized pace, its fastest rate on record.

Now add on multiple rounds of infrastructure bills passed by Congress that are just now beginning to be acted on, and spending by state and local governments is on track to increase for the next several years.

If you're worried about the prospects of recession with a Congress unable or unwilling to support the economy in a downturn, this is reassuring. State and local governments and the federal government are set to spend more, not less, next year because of a mix of their budgetary outlook and already-implemented legislation.

But if you're more worried about inflation staying elevated, this is, perhaps, cause for concern. In hindsight we can say that what the economy needed in 2011 was more government spending rather than the budget cuts we got. So it’s possible that the increase in spending that's going to happen next year is bad timing for the economy, and could cause the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates even higher. It's that possibility—too much government spending at a time of high inflation and rising interest rates, rather than the fears of repeating 2011—that people should focus on.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is founder of Peachtree Creek Investments and may have a stake in the areas he writes about.