Wealthy Americans are again expected to flock to Europe in droves this summer, where they’ll splash out on pricey hotels at the Paris Olympics or in the Mediterranean, vie for Taylor Swift concert tickets and dispense generous restaurant tips. The tourism industry—which contributes 10% of European Union gross domestic product—will be delighted to welcome these big spenders. The locals, though, increasingly look like poor relations, at least in purely financial terms.

While money isn’t everything, Europe would benefit from some soul-searching: Its high living standards are rightly treasured and help explain why it attracts more than half of the world’s international tourists. But these hard-won achievements are at risk unless politicians do more to boost productivity and maintain prosperity.

For decades, Europeans have drawn solace from the fact that while absolute wealth levels are higher in the U.S., we fare better when it comes to other elements of the good life. We enjoy longer paid vacations, less gun crime, healthier diets and walkable cities—factors that in turn contribute to greater longevity. Average lifespans in the European Union are estimated at 81.5 years, compared with around 77.5 years in the U.S.

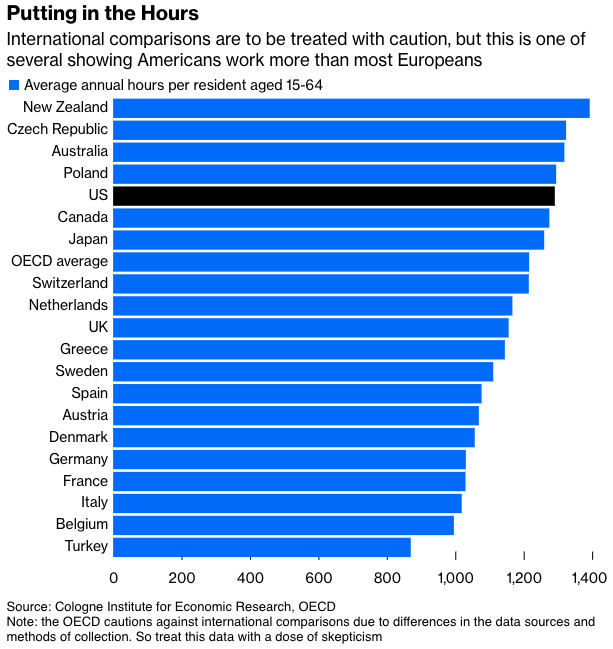

Lately, though, Europe has begun to worry about a yawning trans-Atlantic divergence in economic growth and technological competitiveness. “Americans just work harder,” whereas Europeans are less ambitious and more risk averse, Nicolai Tangen, the head of Norway’s $1.6 trillion sovereign wealth fund, told the Financial Times in April. Prior to stepping down as chief executive officer of Dutch chip manufacturing equipment giant ASML Holding NV, Peter Wennink warned last year that Europe is falling behind and must overcome complacency. “Looking at our society, I sometimes get the impression that we are, as they say, ‘fat, dumb and happy,’” he said.

With Europe’s working-age population set to shrink due to unfavorable demographics, these deficiencies will make it harder to sustain generous welfare systems and public pensions, and to restore the continent’s defense capability in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Voters who feel economically left behind may be more easily wooed by the far right and blame migrants for their woes. Germany is considering ways to incentivize longer working hours, while the U.K. Labour Party has put economic growth and wealth creation at the heart of its election campaign.

But keeping up with the U.S. economic juggernaut isn’t easy: U.K. corporate boards are under pressure to increase CEO pay to match U.S. levels to avoid losing talent and to shift their stock listings to New York where they might get a better valuation. Meanwhile, Le Monde’s New York correspondent lamented in April that the U.S. has become “unaffordable” for Europeans.

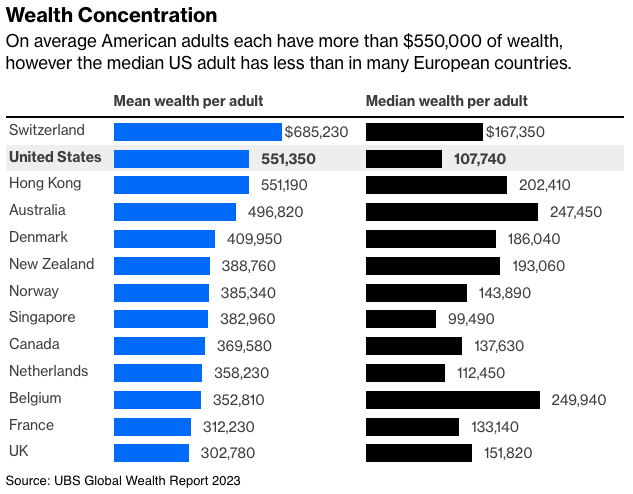

It’s certainly not all gloom and doom on this side of the Atlantic: eurozone unemployment is at a record low, for example. And the U.S. is far from perfect: Much of the transatlantic gap in GDP levels is explained by currency fluctuations, faster population growth and Washington’s fiscal largess (which might not be sustainable). American employees need big salaries to afford shockingly expensive child care, university tuition and health care. And higher average U.S. wealth levels shouldn’t blind one to the fact that this wealth is very unevenly distributed; U.S. median wealth levels tell a very different story, as this chart shows.

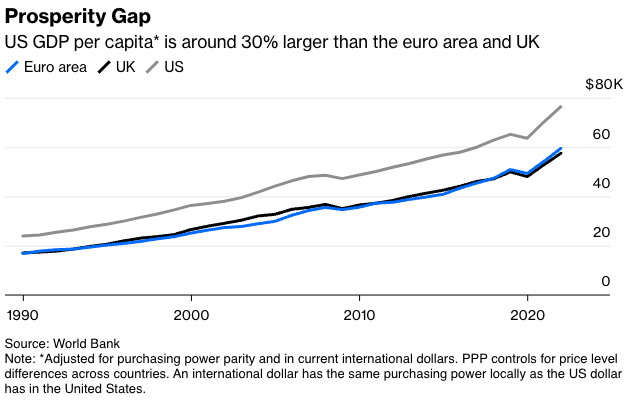

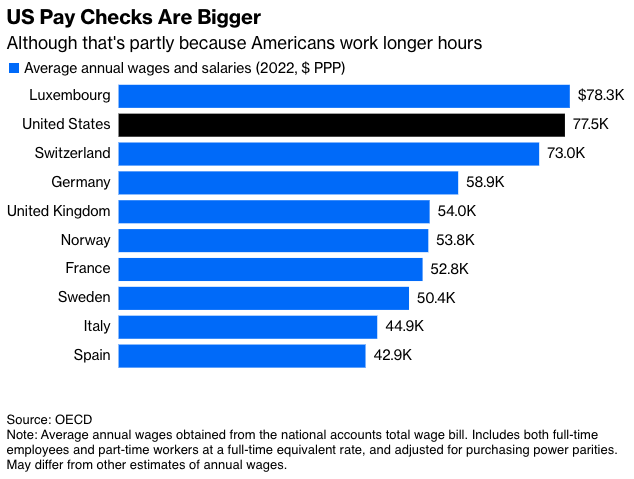

Nevertheless, on several metrics Americans are doing better financially. Adjusted for the cost of living, U.S. GDP per capita is around 28% higher compared with the euro area, according to the World Bank; meanwhile, average annual wages are also superior in the U.S. and labor taxes are comparatively low, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Remarkably, more than one-third of American households now earn over $100,000 a year, according to the U.S. Census Bureau; there are around 23 million U.S. millionaires, compared with fewer than 3 million each in the U.K., France and Germany, according to UBS Group AG’s 2023 global wealth rankings.

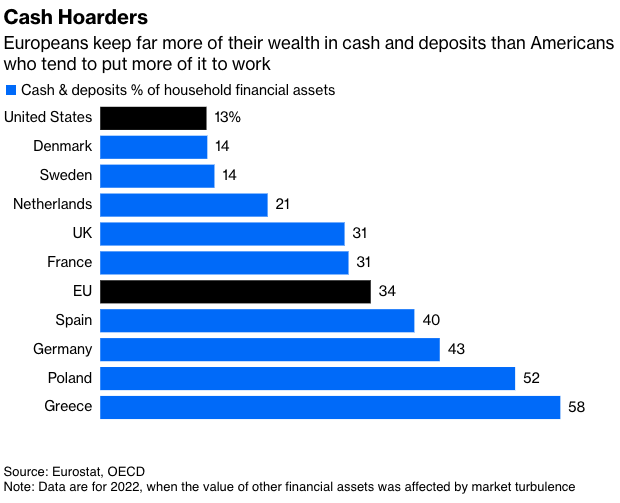

This prosperity gap is partly a result of how Americans invest their spare cash: Thanks to tax-advantaged accounts like 401(k)s, they’re far more likely to buy stocks, while Europeans hoard trillions of euros in low-yielding bank deposits.

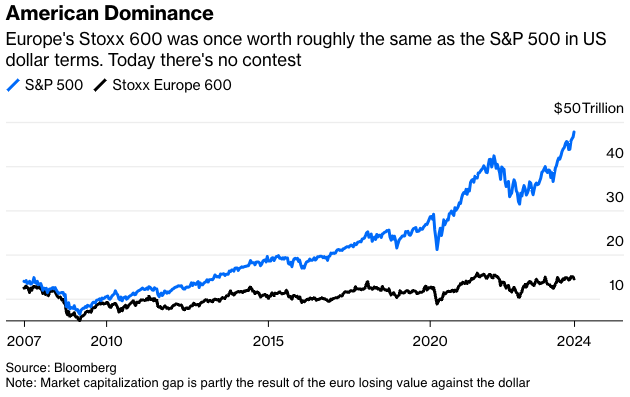

Americans’ greater risk tolerance has paid off. It might seem preposterous now, but in 2008 the market capitalization of the Stoxx Europe 600 was roughly the same as the S&P 500 in U.S. dollar terms; today the gulf is massive. Artificial intelligence chip maker Nvidia Corp., for example, is worth more than the entire French stock market.

A dearth of home-grown European tech champions makes me worried that the trans-Atlantic wealth gap could widen further. Around 70% of foundational AI models are being developed in the U.S., while just three U.S. companies account for 65% of the global cloud computing market, Mario Draghi, the former Italian prime minister and European Central Bank president, noted in a speech last week.

Draghi is due to publish a much anticipated report on Europe’s lagging competitiveness next month: Besides Europe’s comparatively high energy costs and fragmented single market, the main problem is weak productivity growth, he’s warned. A recent report from the European Centre for International Political Economy reached a similar conclusion: “Europe’s economic challenge is not about working longer hours or taking shorter holidays but improving the amount of value-added generated by the inputs to the economy.”

One obvious area to focus on is research and development spending: Between 2014 and 2021 U.S. R&D expenditures increased at twice the rate as those of the EU, the ECIPE report notes.

Mobilizing more joint EU borrowing to help fund such investment could be difficult if Marine Le Pen’s euroskeptic party forms France’s next government. That’s all the more reason to tap private capital, including by nudging Europeans to invest more of their savings in the stock market and thereby support domestic companies—a topic I explored here.

No one should begrudge Americans their hard-earned trips to Europe—it might be the only paid holidays they get all year. In contrast, Europeans need to step up their game if they want to keep enjoying the good life.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for the Financial Times.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.