Investors have been tying themselves up in knots during the past year or so over when the Federal Reserve will start lowering interest rates. Not so the folks at the Intrepid Income Fund, whose fixed-income strategy frees them from fretting the Fed.

The fund’s stated goal is to generate absolute returns while producing current income at a higher yield against comparable maturity U.S. Treasurys. It attempts to do so by investing mainly in short-duration, smaller-cap high-yield credits that are out of favor or under-followed by the broader investment community. The fund’s managers call this their sweet spot.

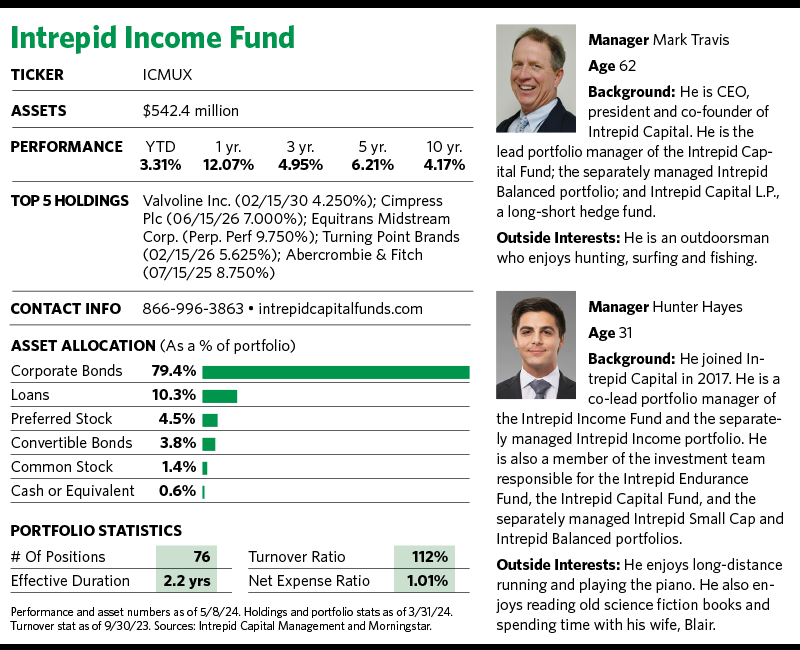

As co-lead portfolio manager Mark Travis notes, he and his team have produced market-beating returns by taking “three-foot puts” focused on investing on the short end of the curve. He and his team posit that focusing on short-duration securities generates consistent income, which translates into monthly payouts for the fund’s investors. The fund’s 30-day SEC yield as of March 31 was 7.9%.

The strategy requires less macro forecasting and gives the managers a higher degree of confidence in return of principal. It also lets them quickly respond to changing market conditions. Because the fund’s returns are less sensitive to interest rate fluctuations, its managers don’t spend a lot of time speculating on the Fed’s interest rate moves.

“We’re positioned either way to take advantage of a lower-rate market or a market with higher rates,” says Hunter Hayes, Travis’s fellow co-lead portfolio manager. “A lot of that is afforded to us by our short-duration mandate. We get money constantly coming back to us that we can redeploy with a new opportunity set based on what we see from a risk/reward perspective.”

Focus On What Works Best

The Intrepid Income Fund has produced a solid track record since the strategy launched in 2007. (The fund’s current institutional class shares began trading in 2010.) During the past 10 years (as of May 8) the fund ranked third for average annual returns in Morningstar’s multisector bond category.

But investors perhaps should focus on the five-year period starting in 2019. That’s when Hayes teamed up with Travis to co-manage the fund. Travis, who co-founded Intrepid Capital Management in Jacksonville Beach, Fla., 30 years ago, had co-managed the fund for about 10 years before he stepped aside. By November 2018 he was back, and Hayes came on board two months later.

Together, they rejiggered the fund to concentrate on what they believe are Intrepid’s strengths. “When you look at the fund before 2019, there were periods when we weren’t fully invested, and at times we would take on non-income risk,” Hayes explains. “When you pulled those two things out of the performance before 2019, the credit-related performance of the fund was phenomenal.

“We decided we needed to lean more into what we’re really good at, which is core credit work,” he continues. “And we do a really good job with the underwriting—picking solid companies to lend money to.”

The duo significantly underperformed the fund’s peers in 2019. “Mark and I had a transition year in 2019,” Hayes says. “It was a pivot year coming out of the prior regime into this one.” Beginning in 2020 the fund has turned in top-tier performance against its category peers and various benchmarks.

According to Intrepid, the Income Fund’s five-year annualized return of 6.16% (through this year’s first quarter) exceeded that of three comparison benchmarks—the Bloomberg U.S. Government/Credit 1-5 Year Index, the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index and the ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index—by roughly 600 basis points each. And it topped the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index by a little more than 200 basis points.

“It’s a case of if you do the same thing everyone else is doing you get the same result,” Travis says. “Obviously, we haven’t been doing the same thing everyone else is doing when we’re up 600 basis points over the past five years and the [Bloomberg Agg] has been virtually flat.”

Hayes notes that investors see the fund’s performance and ask how the portfolio managers were able to call interest rates so accurately. “The reality is that it hasn’t been a call on interest rates,” he states. “We lend for short time periods not because we’re prognosticating on what the Fed is going to do, which is a fool’s errand. It’s a matter of underwriting the companies we think have a high level of certainty to pay us back. That’s good, fundamental core credit work.”

Investors pay up for the Intrepid fund’s outperformance. Its expense ratio of 1.01% puts it in the second-costliest quintile of its Morningstar category. But that hasn’t seemed to deter investors. According to Hayes, the fund’s assets have grown from a little more than $300 million going into 2023 to roughly $535 million recently. “We’ve found good ways to put that money to work,” he says.

Small Is Beautiful

Travis and Hayes take pride in not being index huggers. “The majority of our positions aren’t indexed, meaning they’re not in any index,” Hayes says.

He notes that investment ideas can come from anywhere and everywhere, and they’re always income-centered. The managers prefer what he describes as typical vanilla bonds with coupon payments and a maturity date. “Occasionally, we’ll do something beyond that purview when it makes sense, such as busted convertible bonds or preferred stock or esoteric fixed-income instruments,” Hayes says.

Most of the securities in the portfolio come from smaller high-yield issues of less than $500 million. The Intrepid team believes being small is an advantage here because many bond funds are too large to invest in these smaller issues. They say this can create attractive mispricing opportunities that they’re able to exploit.

Intrepid seeks companies that generate free cash flow and have returns on invested capital that exceed the cost of their debt. The fund also favors companies with a favorable debt-to-enterprise value ratio, which measures a firm’s equity cushion. “We think about liquidity parameters relating to a company’s ability to pay us back,” Hayes explains.

The two managers also want to own mature businesses with understandable business models and recession-resistant products that they can value with a high degree of confidence. And they like companies whose management teams have acted in the best interests of shareholders and bondholders.

Travis and Hayes work in tandem with Matt Parker and Joe Van Cavage, both of whom have worked on the fund for the past five years. Earlier this year they were elevated to the title of co-portfolio managers, with Travis and Hayes listed as co-lead portfolio managers.

They have a universe of 10,000 eligible securities on their screens as fund candidates. But their winnowing process trims the list of viable candidates to a very small fraction of that.

Whoever finds an idea pitches it to the group, and as a group they decide whether it’s worth pursuing further. If so, the next step is crafting a five- to 10-page write-up on the company. Then one person is assigned the role of devil’s advocate and tries to poke a hole in the thesis. Ultimately, any names added to the portfolio must be unanimously approved.

“If a name doesn’t make it into a portfolio it goes on our shopping list, and when the time is right maybe we’ll revisit it,” Hayes says. “So it’s not wasted work in our opinion, it’s just deferred work.”

Intrepid looks for companies whose bond prices are depressed because, in their view, the market has unfairly punished them for issues the portfolio managers believe are temporary or fixable. That creates an opportunity to buy at attractive yields.

“I think it’s very much a credit picker’s or risk asset picker’s market,” Hayes says. “Not all companies or high-yield bonds are created equal. We think we earn our stripes by finding the treasure amidst the rubble.”

Concentrated Portfolio

The end result is a concentrated portfolio generally consisting of just 40 to 50 names, which is much less than the typical fixed-income fund.

“We don’t think there’s much diversification benefit beyond 50 or 60 names,” Hayes says. “Our view on this is we should stand behind our research, and if we want to get the benefit from the alpha we’re generating from our research we need to be this concentrated.”

Despite its narrower focus, the portfolio is still energetic, with a high turnover rate—which it recently reported at 112%.

Travis says that turnover reflects the fund’s duration, which was 2.2 years as of the first quarter. (Shorter duration fixed-income securities typically have shorter maturity dates, leading to quicker turnover.) That’s compared with 3.3 years for the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index and 6.1 years for the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. That means the Intrepid fund turns over its portfolio at a faster rate than funds more closely tracking either of those indexes.

But high turnover means less tax efficiency. Hayes says tax awareness is part of his management team’s thought process, and they look for ways to be efficient, but it’s not something they prioritize. “Our investors think about it and it’s part of their calculus. Obviously with the turnover there are tax implications,” he says. “Our view, and our investors agree with that, is that it’s more than offset by the alpha that we’re generating through these short-dated opportunities.”

He posits that the fund’s turnover is one of the big reasons for its success. “We have money coming back to us, which allows us to reassess the state of the world as things change.”

Travis offers that the fund’s high monthly distribution yield of roughly 8% makes it a good fit in the fixed-income portion of a tax-deferred or tax-advantaged account, like an IRA, where the dividend income can accumulate on a tax-deferred basis. “Though we believe that the fund’s income profile is attractive even on a tax-adjusted basis,” he says.

Hayes says a number of large advisory investors have made the Intrepid Income Fund part of their core fixed-income holdings because they agree with the portfolio managers’ contention that short duration—in tandem with prudent credit picking—is the right strategy for risk-adjusted returns right now.

But what happens when the Fed eventually starts cutting interest rates and long-duration bonds become a more attractive option (if they aren’t already as investors anticipate lower rates, which would boost longer-duration bond prices)?

“If you have a strong view on what the Fed is going to do, then go for it,” Hayes says. “Our view is that maybe if … you’re getting equity-like returns for high-quality credits, then it gets interesting and maybe then we’ll start to nibble at some of the medium and longer-duration opportunities. But right now, in our view there’s no argument that [shorter duration] is a better place to deploy capital in the fixed-income world. Hence, we think we belong as a core option.”