Special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) have fast become popular ways to tap the new issue market, popping up in the financial news with regularity. But are they good investments?

The quick answer is they are not the best choice for every investor, nor for every transaction.

A SPAC raises capital through an initial public offering (IPO). Also known as "blank check companies," their purpose is to acquire existing companies; they have no commercial operations of their own initially.

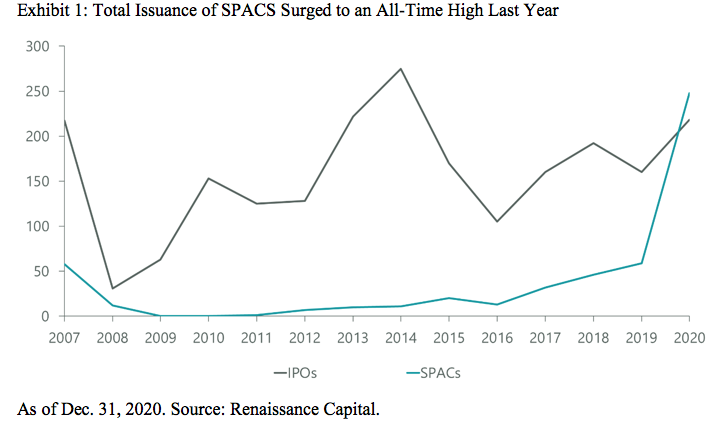

Statistics bear out their growing popularity. More SPACs went public in 2020 than traditional IPOs, the first time that has ever happened, according to Renaissance Capital.

According to SPACInsider.com, 248 SPAC IPOs raised more than $83 billion in 2020. That compares to 59 deals in 2019 that raised $13.6 billion. Year over year, the average SPAC IPO debuted at $335 million, up from $230 million in 2019.

When SPACs were introduced about 15 years ago, the volume was relatively low; they were not meaningful avenues for companies to list their securities. But that has changed. In fact, “unicorns”—private companies with an implied valuation of $1 billion or more—are often associated with SPACs. Some high-profile names include DraftKings [NASDAQ: DKNG], Nikola [NASDAQ: NKLA] and Virgin Galactic Holdings [NYSE: SPCE].

A new group of sponsors—many with boldface names—has legitimized the SPAC process. Billionaire investor Bill Ackman raised a record $4 billion in July for his Pershing Square Tontine Holdings fund, indicating how much investor appetite for SPACs has soared. Bill Foley, owner of the National Hockey League’s Vegas Golden Knights, is a SPAC veteran who has been aggressive in raising new capital and looking for deals. Other well-known investors in the space include Oakland Athletics’ president Billy Beane, the inspiration for Michael Lewis’ baseball-as-business book Moneyball, and former U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Paul Ryan.

By offering the guidance of experienced partners, SPACs can offer companies a faster path to going public. It doesn’t hurt that this route is less susceptible to the vagaries of the traditional IPO process.

What kind of acquisitions do SPACs target? Any kind of companies their management teams believe will be good investments. But management may not have specific acquisition targets in mind when they raise capital. This is one of the reasons do-it-yourself investors may want to think twice before jumping into SPACs. Without some familiarity into the investment track record or industry focus of a SPAC sponsor—information that may not be as readily available as data on public companies—an investor could be surprised about what they are getting in a SPAC.

SPACs ordinarily have two years to complete an acquisition or they must return investors’ funds. The good news is that if investors don’t like a proposed acquisition—if they deem it a poor deal based on whatever yardstick they use—they can vote down the deal or sell their interest in the SPAC and get their original capital back.

Despite that safeguard, it’s a different risk/reward profile than participating in an IPO or buying other publicly traded securities. This is one of the factors investors should carefully consider before putting up money.

As professional investors, my team and I manage over $12 billion across multiple strategies with SPACs representing about 3% of assets in one of our strategies but less than 1% overall. We have looked at a number of SPACs over the last several years, but participated in just a few where we knew the managers very well and expect them to target alluring disruptive businesses. We seek out SPACs hunting for high-growth companies in industries experiencing nice tailwinds and offering manageable debt and tremendous potential for operating margin expansion. And, as with any investment we make, the quality and motivation of the company’s management team is a huge factor.

What do our SPAC holdings have in common? They’re managed by experienced, smart, creative investors we know and respect. We’re confident they’ll go out and buy a business with the potential to create long-term value.

Special.

Aram Green is a portfolio manager and managing director at ClearBridge Investments, a subsidiary of Franklin Templeton.