In spite of the highest Federal Reserve policy rates in two decades, the U.S. economy grew about 2.5% last year, unemployment remains low and stocks are near all-time highs, leading many observers to conclude that the economy must have become less interest-rate sensitive—and probably needs permanently high benchmark rates to prevent overheating.

Consider the monumental shift in attitudes in recent months. For the better part of a decade, market economists have generally believed that the longer-run “neutral” Fed policy rate—consistent with low inflation and sustainable growth—was around 2.5%, and that remained the case even after inflation surged in 2021 and 2022. Once inflation had been beaten, economists assumed that policy rates would eventually “normalize” around that 2.5% level. But in 2023, something snapped and economists’ median views started to drift up.

As of the latest survey of primary dealers conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the median respondent now sees rates settling at around 3%—a tectonic shift in the world of central bank forecasting. In options markets, traders are wagering on rates staying at around 4% into at least 2026. Market participants don’t just think rates will stay at their current extremes for longer than previously anticipated; they now also believe that rates may have to stay moderately high forever—a shift that implies far-reaching consequences for housing affordability, corporate finance and the national debt.

But with all the moving parts in the economy today, can economists really know how interest rates will shake out that far in the future? I’d argue that many of these projections miss the particular and fast-changing circumstances of the current moment.

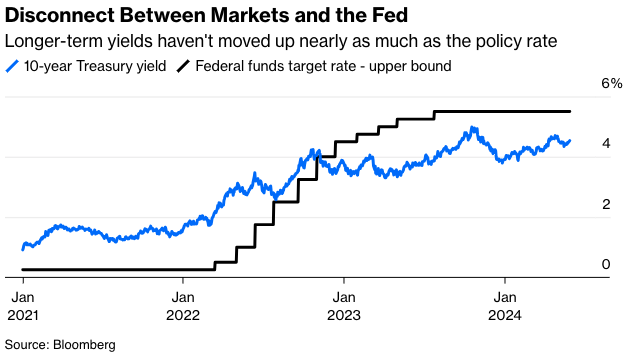

Any explanation of the muted impact of rate hikes has to start with longer-term Treasuries. The 10-year Treasury yield is what drives the most important consumer and corporate borrowing costs, not the fed funds rate, and it hasn’t tightened nearly as much as the latter—a historical rarity1. From March 2022 to July 2023, the Fed raised policy rates by 525 basis points, but 10-year yields increased just 172 basis points. Even counting from the lows in 2020 to the highs in 2023, the 10-year only covered 448 basis points of territory. For most of the hiking cycle, investors and traders have been looking six months ahead to expected rate cuts that never seemed to materialize. At first, those expectations were driven by recession forecasts, and, later, by the belief in an imminent soft landing.

But policy rates and 10-year yields are unlikely to remain inverted forevermore. On the contrary, if inflation abates painlessly and the Fed cuts rates, you’d expect—all else equal—the yield curve to normalize and 10-year yields to fall less than the policy rate2. Just as longer-run yields have been less restrictive than expected during the tightening, they could be slightly more restrictive than you might expect during the easing. We have no reason to conclude that the transmission mechanism has broken down; the timing may simply have changed.

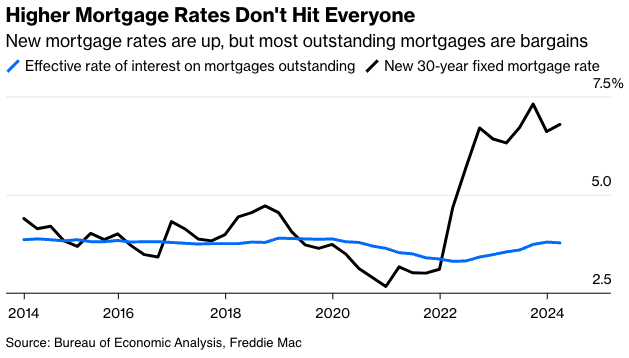

The second key issue is the “lock-in effect.” During the pandemic, consumers and businesses alike locked in ultra-low fixed-rate borrowing costs, effectively shielding themselves from higher rates. Fixed-rate borrowing has long been a feature of the US economy, but the past four years were different because of the breakneck speed at which the economy shifted gears from a fast and deep recession in 2020 to an inflationary expansion in 2021. The effect won’t last forever. Already, businesses are rolling over debt at higher rates, and the effective mortgage rate on outstanding residential loans is creeping higher.

The slow process by which that’s happening may well be a reason for policymakers to hold rates at the current level for a while, but this dynamic isn’t permanent and is unlikely to repeat itself in future tightening cycles.

That’s why I’m not on board with the near-universal adoption of the “higher rates forever” thesis. As of the latest primary dealer survey, even the bottom 25% of the economist distribution now see the longer-run neutral policy rate drifting up to 2.75%. In the SOFR options market, current pricing implies just about a 30% probability of the Secured Overnight Financing Rate getting back to around 3% or lower by 2026. Given what we know today, those odds strike me as a bit off balance.

We’ve just gone through an extraordinarily unique period in world history, and the economy is behaving in bizarre ways—but probably just for the time being. It’s always worth treading carefully when folks tell you that the world has fundamentally changed forever.

Jonathan Levin is a columnist focused on U.S. markets and economics. Previously, he worked as a Bloomberg journalist in the U.S., Brazil and Mexico. He is a CFA charterholder.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.

1 While policy rates and yields on 10-year notes have been somewhat out of sync for decades, history shows that the 10-year yield habitually climbs high enough to kiss the Fed's peak rate in a given hiking cycle. In 1994-1995, the 10-year peaked at 8.03%; the upper bound of the fed funds target peaked at 6% about two months later. In 2000, the 10-year peaked at 6.79%; the fed funds peaked at 6.5% about three months later. In 2006-2007, the 10-year had a double peak at around 5.29% over about 12 months that coincided almost perfectly with the peak in fed funds at about 5.25%. In 2018, the 10-year peaked at 3.24% before the fed funds peaked at 2.5% about a month later. This time, fed funds rose to 5.5%, but the 10-year yield only grazed 5.02%.

2 In 2005, Alan Greenspan lamented the "conundrum" that 10-year yields weren't moving much, despite 150 basis points of federal funds rate increases. Of course, inflation measured by the PCE ultimately fell back below 2% anyway, and the fear that higher rates weren't transmitting properly eventually gave way to a much more pressing challenge: the financial crisis.