This year’s Nobel prize in economics was awarded to Richard Thaler, a pioneer of behavioral economics. But there is a tale told by a lesser known Nobel laureate, Kenneth Arrow. As a World War II weather officer, he was tasked with analyzing the reliability of the army’s long-range weather forecasts. His conclusion: statistically speaking, the forecasts weren’t worth the paper they were printed on. Captain Arrow sent along his report only to be told, “Yes, the General is well-aware the forecasts are completely unreliable. But, he needs them for planning his military operations.”

Okay, maybe you don’t actually need a Nobel prize to know that rationality in the decision-making department is often lacking. Case in point: the capital markets. While subtle and ingenious in construction, the capital markets are, nonetheless, driven by the mass action of millions. They are a reflection of ourselves and necessarily express both the summit of our knowledge as well as the pit of our fears, and everything else in-between. And, this brings us to the subject at hand: Gresham’s Law. Sir Thomas Gresham was a financier in the time of King Henry VIII and his name is, of course, attached to the principle that “bad money drives out good money.” Coin collectors of a certain age are familiar with the near immediate disappearance from circulation of all silver American coins once Congress had mandated the use of base metals beginning with the 1965 vintage. While all coins—silver and copper alike—carried identical legal tender value, it was the silver coins that vanished. Perhaps you are wondering what this has to do with bond investing? Everything!

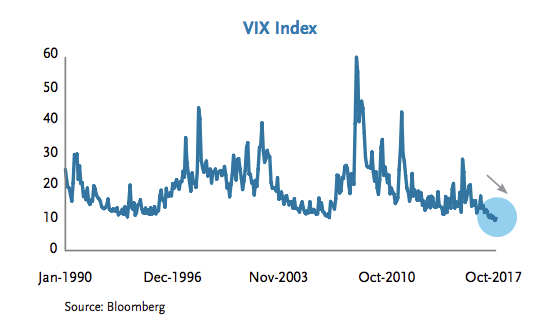

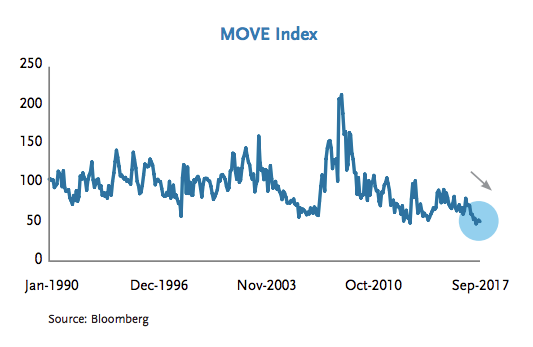

Consider the state of financial markets as witnessed by metrics of implied volatility:

Both indices hover at generational low levels. If markets were “run” today by humanity’s better angels of wisdom and rationality, you would have to conclude that Mr. Market has drawn on his collective insight and pronounced the capital markets to be safer now than at any other time in the past quarter-century. That is a stunning conclusion! But if rationality can’t explain a 25-year trough in expected risk, then we must necessarily conclude that there must be some other, less rational explanation. How about this: investors are, by and large, famished for yield and willing to underwrite most any risk to get some income. In short, the marginal price setter is “irrationally exuberant”, or dare we say it out loud? “Greedy.”

So, the age old tension that presents itself is this: there are those investors, the “value tribe”, that resists the general lowering in underwriting standards that comes with the aging cycle. The value guys believe that their principal is always precious and is best “wagered” when the return/risk profile is asymmetrically biased in favor of the investor. The “momentum tribe”, in contrast, tends towards a belief that your capital must be kept working, otherwise “yield” is “needlessly” sacrificed.

Does it not stand to reason that, late in the asset price cycle, that the “momentum” money drives out the “value” money? Yes! Capital that lowers its hurdle rate of return and adapts itself to loose underwriting criteria will necessarily bid up asset prices to levels that become inconsistent with the criteria applied by the more discriminating pools of capital. The “clad” underwriting drives out the “silver.”

Now, admittedly, a win is a win, and momentum has been the winning trade. Whether intrepid or fool-hardy, “risk on” has won the year 2017. But do trees ever grow to the skies? Did Minsky not elucidate how extended periods of low volatility have the effect of masking financial pathologies, allowing them to metastasize throughout the system? Indeed! While the central bankers dream of a never-never land where wise scholars can direct the flow of irrational humans, the real world that the rest of us inhabit is decidedly messier.

How so? Long periods of low volatility often mean that some traders and fund managers become less concerned with closely scrutinizing what they own. Credit analysis is hard, and in an environment where prices become inelastic to the “fundamentals,” some conclude that the work involved in analyzing bonds is a case of the juice not being worth the squeeze. Low volatility environments remove incentives to trade, thereby degrading the quality of price information.