A quandary of writing a weekly letter is I notice myself saying the same things repeatedly. Something comes to mind as I write, I start to include it, and then I vaguely remember, “Wait, didn’t I say that last month/quarter/year?” I check and sure enough, it’s right there. Should I say it again?

There’s no clear answer to that. Some readers will notice the repetition and call me Johnny One-Note. But others need to hear a point several times before it sinks in. This becomes a judgment call. If I think it’s important enough, I’ll repeat myself and take the criticism.

Today, for example, I will again say something I observed just two weeks ago: Inflation is both better than it was and higher than it should be. You must recognize those two points to know where the economy is and where it’s going.

Another thing I often note is that inflation is individualized. Everyone experiences it differently based on their situation. But one thing is consistent. As time passes, the “better than it was” aspect fades while the “higher than it should be” part takes over.

We see this in public opinion and consumer sentiment surveys. Paul Krugman, Jared Bernstein, and so many others wonder why people don’t feel better than the polls and surveys suggest. They have a point. Unemployment is close to an all-time low, wages are rising, GDP is still growing modestly, inflation is falling, the stock market is pushing all-time highs and continues to make even new and higher highs, you can get 5% on your money market accounts, and so on.

All that notwithstanding, millions say their situations are getting worse and they aren’t happy about it. Moreover, they aren’t wrong. I’ve talked before (see, I’m doing it again) about inflation having a cumulative effect. Prices may be rising more slowly, but they’re still higher than they were and certainly not falling. That hurts even if inflation is “only” 2%.

Data is important but not everything. Perceptions matter, too. Today we’ll look at how people feel inflation and what it may mean in the years to come.

But first, and really quick, I want to thank the hundreds of people who sent in title suggestions for my new book. I literally sorted through multiple hundreds of potential titles and have narrowed it down to five titles and five subtitles. You can click on this link and take a 20-second survey on which title and subtitle you like.

Don't think about it too much—just which one or two resonates with you. Then do the same for the subtitles. After that, there will be a section where you can send any comments. I will read every one of them. Thanks in advance.

Can’t Get No Satisfaction

Inflation isn’t perceived in a vacuum. It is one of many conditions that combine into a general sense of happiness, or lack thereof. We have to consider the entire milieu.

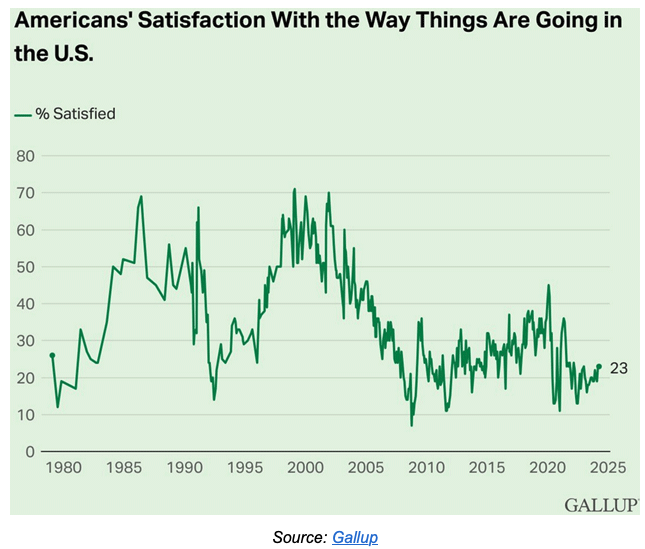

According to Gallup, Americans have been generally grumpy for two decades now. Their regular monthly survey series shows public satisfaction with “the way things are going” was over 70% at the turn of the Millennium, then dropped below 50% in 2004 and is now down another 20 points to only 23%. Ugh.

The way this series evolves is instructive. Public satisfaction was also quite low when the data begins in 1980—also a period of high inflation. But feelings improved throughout that decade, then fell again in the early 1990s. That was a recessionary period and is one reason George H.W. Bush lost to Bill Clinton in 1992. Then it fell a third time in the early 2000s, leading to the 2008 recession.

But that time, it didn’t recover much. A majority of Gallup respondents have been dissatisfied in every survey since 2004. Why? What has kept us continuously net-pessimistic for 20 years now? I don’t know. But whatever it was seems to have preceded the more recent political divisions—and may have helped cause those divisions.

This is important to understanding inflation perceptions. Many who are now upset about inflation (with good reason, as we’ll see below) were already upset long before inflation became a problem.

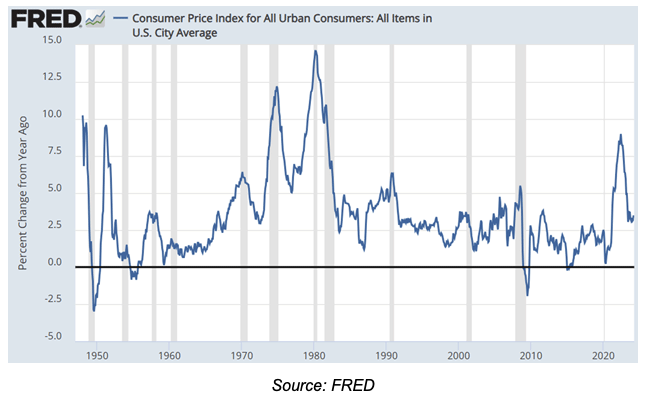

We should also note inflation, while not a new phenomenon, is a new experience for most people. They simply haven’t lived as adults through anything like 2021–2023 or, if they have, only saw it decades ago.

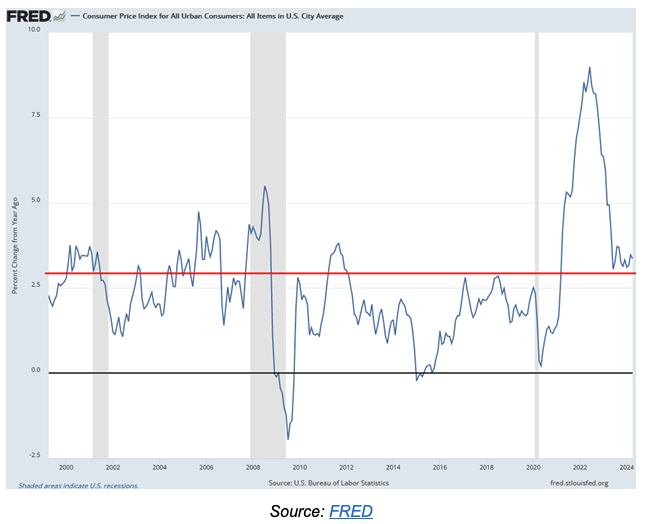

This chart shows CPI’s annual rate by month for the last 25 years. I drew a red line at the 3% level.

Notice how inflation stayed below 3% for long stretches in the early 2000s. Then, other than 2011, it was below 3% and at times near 0% from late 2008 until the Covid recovery began in 2021. Now the former 3% ceiling looks more like the floor.

Just for fun, let’s look at inflation since WW2. There is clearly some correlation between the mood of the country (Gallup poll above) and inflation. It’s not perfect, of course, but inflation is clearly important.

Compared to anything seen in the adult lives of today’s consumers under 65, three straight years of 3% or higher inflation is simply unprecedented. It is remarkably worse than anything they remember. In fact, what they remember is often falling prices for many products, since this was also the period when low-priced Chinese goods were flooding into U.S. stores, as well as high productivity which meant lower prices. I have written letters on the “bad” kind of deflation. But…

If, for most of your life, you hear “inflation” described mostly as something that never happens anymore, and then it suddenly starts happening, of course you are upset. You face a new and troublesome problem that’s not your fault and is largely uncontrollable. You thought it would never hurt you. Yet it is.

Headache List

The Federal Reserve’s annual household survey, just released but conducted last October, found 65% of U.S. adults said rising prices had made their financial situations worse, including 19% who said it made their situations much worse. I haven’t seen crosstabs, but I feel sure this group skews young.

My eight children are a readily accessible panel of young adults. They have all built independent lives of which I’m quite proud, but they share many of their generations’ problems, too. When I reached out to ask how inflation is affecting them, they almost blew up my phone with long, impassioned text messages.

Some background: I have two biological daughters and adopted five children. My wife Shane added another young man. Their ages range from 25 to 47. All told, I'm a father to two black sons, two Asian daughters, a blonde, brunette, redhead and a card-carrying Choctaw Indian. Nine grandkids with more shots on goal coming. Only one is 100% Caucasian. The rest have some hyphen in their ethnicity. Four graduated college. Two are STILL(!) working at it. Three have serious life-threatening health issues. All are working and decidedly middle class, although some would argue they only wish they were middle class. They don’t feel middle class.

I think they are a good proxy for cross-culture America. With the caveat these are anecdotes, not data, I’ll share some of their (slightly edited) thoughts below. I suspect you would get similar responses from your own family networks.

As you might expect, housing prices were high on the headache list. This is the single biggest expense for most households and my kids are no exception.

Amanda: “A starter home (3 BR/2 BA) in Tulsa back in 2014 when we bought ours was $97,000 with a 3% mortgage rate. Now the same kind of homes are $265,000 with 5–8% mortgages.” (Note: This would represent a 173% price increase in 10 years, plus the higher mortgage rate now.)

Tiffani: “To lease a house in Frisco (Dallas area), they wanted a two-year lease with a 5% increase after year one. I negotiated and it’s now a two-year lease with a 5% increase on renewal. Plus utilities… two years ago I could get electric service for about 10 cents/kwh. Now the lowest I can find is 15–16 cents.”

(For those in other states, parts of Texas have a competitive system where you can choose your electric provider. Though in this case, it seems the competition isn’t exactly bringing prices down.)

Melissa: “Average rent for a 1-bedroom in Austin is $1,642. It was $1,200 in 2020. And to qualify to rent an apartment you have to make three times rent so to qualify to rent a one-bedroom in Austin right now you have to make almost $30 an hour.”

Trey has been hunting for a place for several months. He is now renting a house for $2,000 in an almost country suburb of Dallas and will add some roommates to bring costs down. Chad just downsized even with a new kid. Dakota is living in a nice mobile van with his SO to keep costs down as he goes to welding school. Abigail tells her siblings to check out Habitat for Humanity, talking about lower costs and subsidized interest rates.

Housing inflation is even more frustrating because the benchmarks so badly understate it. Home insurance rates are up more than 40% since 2019 but are not included in CPI and only partially in PCE.

Car insurance is a problem, too, which even The New York Times is noticing:

“The cost of buying and owning a vehicle constitutes a substantial chunk (about 10 percent) of the entire Consumer Price Index used to track US inflation. From January 2020 to January 2024, the cost of a new vehicle rose more than 20 percent, and the cost of used cars was up even more, while vehicle repair overall increased 32 percent. Shortages of computer chips and other supply-chain issues had a brutal impact on auto production and created bottlenecks that drove up purchase prices, which in many cases haven’t gone down.

“In that context, the increase in vehicle insurance premiums of about 40 percent since December 2019 ‘appears reasonable,’ said Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.”

Really Mark? Tell that to my kids and then stand waaaay back… Greedy companies making more profits than ever… (Gentle readers, I try but sometimes words just don’t trump the reality of their bank accounts.)

More prosaic household goods are no better. Tiffani can prove it, too. When she finds a product she likes, she sticks with it and keeps track of the price. She can tell you exactly what she paid years ago on scores of items. For example… (Note that overall inflation has been roughly 23% since 2019.)

- Amazon brand “Presto!” ultra-soft toilet paper (24 rolls) was $22.25 in September 2020, then $28.76 in May 2024, for a 29% increase in five years.

- Royal Canin Persian Cat Food was $29.69 in July 2020 and is $45.99 now, up 55%.

- Nutella (26-ounce jar) was $4.98 in June 2021 and $8.99 in May 2024, an 81% increase.

- Nilla mini vanilla wafers were $4.39 in May 2019, $5.99 now, a 36% increase.

Tiffani’s comment on her data:

“These are regulars in our pantry, so all have increased more than inflation with income staying the same. I typically search Google for my regular product and then go with whoever has the lowest price. NONE of their prices are increasing at the 3.4% reported inflation rate. Though I will say a prescription I’ve been taking since 2022 has remained $23.09 without insurance.”

She also notes hay prices (she works with and owns a few horses) have doubled or more in the last five years. Her sources at the Humane Society say “equine surrenders” are very high right now, with many people saying they can’t afford feed and are having to thin their herds. More animals than ever are being put down.

I could go on, but you get the point. The lower and middle classes feel inflation far more intensely than well-paid professionals, wealthy executives, and the top 25%. Those in the top tier may observe something costs more, and probably grumble about it (like me and my neighbors), but that’s all. They don’t have to do without, nor do they have to use what should be leisure time to shop around for the lowest price on basic living needs.

“A little inflation” is not good, no matter what economists tell you. Even 3% hurts a lot. And as Tiffani’s data shows, it is often way more than 3%.

No Political Solution

Felix Salmon had a really perceptive note last week on why inflation is so confusing. He thinks the word itself has been redefined.

“The meaning of the word ‘inflation’ has changed. It used to mean rising prices; now it means high prices.

“Pedants, economists, and style-guide editors might not like it, but if you want to understand what people mean when they complain about inflation, you need to understand how the vernacular has evolved over the past couple of years…

“The headline measure of inflation is based on something pretty arbitrary—where prices were exactly one year ago… A more intuitive concept of inflation is just ‘Am I paying higher prices for things than I used to.’”

Again, let’s remember the math here.

If (just using round numbers) the inflation rate rises from 2% to 20%, stays there a year and then drops back to 2%, economists will tell you inflation is over. But you are still paying 20% more for everything you need, and will keep doing so forever, barring a bout of actual deflation (which I promise you don’t want, but that’s another subject).

If you could somehow magically arrange for everyone’s income to rise exactly in line with their living costs, people might feel better. But that never happens, at least in the aggregate. People just see the media and politicians telling them inflation is better when it’s not better. They’re still paying more while often making the same or even less. That dog won’t hunt, as we used to say in West Texas.

And worst of all, there is almost no reason to expect the price increases to stop, much less reverse. This robs people not just of money, but of hope. It’s no wonder they are grumpy and looking for a change.

Then the question becomes what sort of changes, if any, would help. To answer that we need to consider what produced the initial inflation.

As always, many factors contributed. The broad outline is that Covid and its associated policy responses both impeded supply and stimulated demand. This happened in erratic, unpredictable ways that kept producers from responding effectively. The virus itself also reduced labor supply (and still is as millions suffer from “Long Covid” disability). Higher prices were the natural result.

Fiscal stimulus, particularly the third round that Biden and the Democrats passed in 2021, aggravated this inflationary situation. This is clear in the monthly CPI data, where you can see prices increasing in 2021 as checks went out to households and unemployed workers received extended extra benefits. Inflation was already well underway long before the Russia-Ukraine war began, though the war and its sanctions didn’t help.

If Biden wins reelection and control of Congress, we can expect more such stimulus, though it will take different forms—new healthcare and childcare benefits for the middle/lower classes, for instance. These will further increase the government debt and keep interest rates high. They might even spark recession, reducing inflation the hard way.

Trump with a Republican sweep would have less predictable results. But simply going by the policies he’s stated, more inflation is the likely outcome there, too.

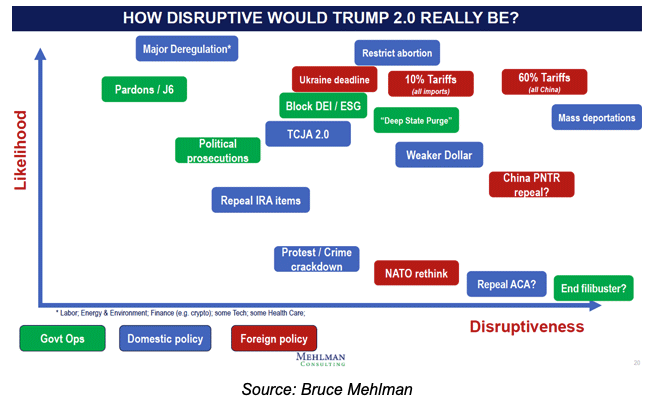

Here’s an interesting chart from Bruce Mehlman’s latest deck. (His quarterly decks are a stop-and-must-read for me.) He plots Trump policy promises by his estimate of the likelihood they will happen vs. their level of disruption. That means the top right area is the big changes that could actually happen.

In that area we see big tariffs on China, smaller tariffs on others, mass deportations, repealing China’s “most favored nation” status (“PNTR”) and a weaker dollar. All those would be inflationary, though the degree would depend on many details.

Further, part of the “Deep State Purge” might involve the Federal Reserve. If Trump seeks to force the Fed to cut interest rates as much as he would like (as he talked about in his first term), that will be inflationary, too.

Can either party win a clean sweep? It is still 160 days out and anything can happen. The more probable outcome is some kind of divided government with the president, Senate, and House unable to do much unless they make deals all sides will hate. It would likely mean more of the same gridlock that prevails right now, letting the current problems continue.

In any scenario, inflation doesn’t really have a political solution. It is solvable, though. Productivity-raising artificial intelligence breakthroughs could change the outlook, as would anti-aging and other healthcare breakthroughs. The new generation of weight loss drugs is already having an effect. More may follow.

For now, and probably a few more years, inflation and the high prices it has brought are unlikely to improve much. I don’t like saying, “Get used to it.” But it’s the best advice I have. Thanksgiving will be interesting this year.

John Mauldin is co-founder of mauldin economics.